LinkUp Forecasting Strong Job Gains in February Even As Labor Demand Continues to Decline

The economy is cooling off a bit but labor demand and monthly job gains remain well above pre-pandemic levels and job gains in February will surprise to the upside

Surprising to no one, the raging debate about the state of the economy, the direction it's heading in, what the Fed should do about it, and what the Fed will do about it continues to escalate to unprecedented levels of intensity, divisiveness, and animosity. Things reached a fever pitch last week when the Commerce Department released PCE data for January indicating that inflation had re-accelerated by 10 bp to start the year, climbing to 5.4% from 5.3% in December, while the core index rose 4.7%. This infinitesimal but unexpected deviation from inflation's consistently smooth decline over the past 6 months or so was enough to send shockwaves through the markets and set off a new wave of apoplexy among those who, believing that the cowardly Fed is abandoning its post in the war on inflation, are adamant that Powell double-down in annihilating the economy enemy.

In a Feb-24 NYT article, an analyst at TD Securities bemoaned, "In a nutshell, it means the job is not done — in fact, it is far from done, because inflation is much too high. The economy is still strong, and consumers are still spending money.” Apparently we need to torch everything to the ground until not a single consumer is left standing with a single discretionary dollar.

The Journal echoed precisely that sentiment in Feb-25 Op-ed, "We can all hope this is merely a short-term inflation setback, like World War II’s Battle of the Bulge, in what will be a glorious victory in the larger campaign. But it’s worth noting that many of the same folks who claimed that inflation was “transitory” in 2021 have been declaring premature inflation victory in recent months. Better to keep fighting until the enemy finally surrenders."

Setting aside the absurdity of putting too much stock in any one month's data point, especially in an era where we're in such uncharted territory, there is no doubt that the data these days continues to support a widening range of perspectives as to where inflation is likely to be heading in the months ahead. What is quite clear, however, is that the economy as a whole, while slowing down a bit, remains quite strong. Perversely, it's the resilience of the economy, and particularly the labor market, that is driving such divergent views as to where inflation might be heading.

And of course, the labor market continues to stand as the strongest pillar in the economy, seemingly impervious to the Fed's rate hike bombardment. In January, hiring surged, unemployment hit a 53-year low, jobless claims remained near historic lows, and wages rose 0.9%, more than double the rate of increase from December.

But as to rising wages and a jump in household income, January's data contains some particular anomalies. Wages rose, in part, because minimum wage increases enacted last year came into affect in more than half the states across the country, and household incomes were boosted by an inflation adjustment to social security payments for 70 million Americans at the start of the year.

Anomalies aside, it's wage inflation that is causing such histrionics in the Fed, the markets, and corporate America. It's baffling how fervently the most strident anti-interventionist, free-market advocates object to an efficient, free, high-functioning, and highly liquid job market. To be fair, corporate America was the first to capitulate (as we knew they would) when they finally started raising wages to fill vacancies after having exhausted all other options. But the Fed, with the markets providing suppressing fire, is still fighting ferociously to regain the ground ceded to employees over the past 2 years.

As the WSJ noted last week, "Fed governor Philip Jefferson said Friday that he saw greater evidence that the central bank would face a long inflation battle because strong hiring and wage gains could sustain firmer price pressures.

“The ongoing imbalance between the supply and demand for labor, combined with the large share of labor costs in the services sector, suggests that high inflation may come down only slowly,” he said at a conference in New York."

But as we first wrote in July 2021 and have noted repeatedly in the subsequent 18 months, the pandemic was a seismic event that fundamentally altered the labor market landscape and, among other things, rendered a tectonic bid-ask chasm between employers and employees that could only begin to be bridged when employers caved to calls for not only for higher wages, but better benefits, improved work conditions, broader adoption of remote work, more worker-friendly policies, stronger corporate cultures, and virtually every other demand being made by workers.

Over the past 13 months, with all those concessions thoroughly deployed across the economy and, most critically, wages heading steadily upward, the U.S. added 5 million jobs to the economy (after adding 7 million jobs in 2021) at a monthly rate more than double the rate of job growth seen in the 3 years prior to the pandemic.

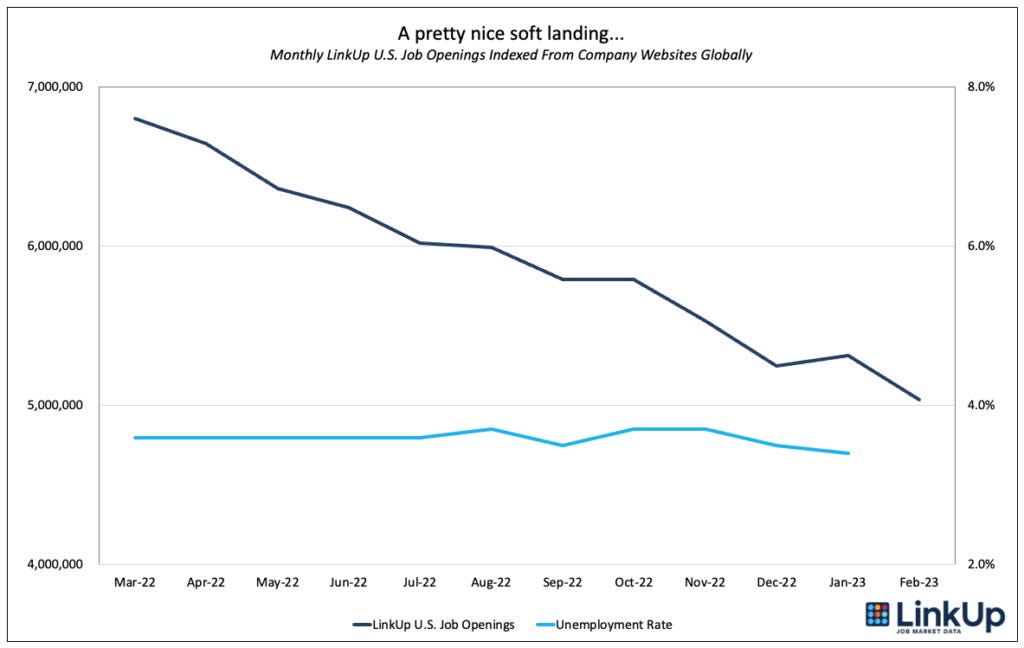

At the same time, the Fed began aggressively hiking rates in an attempt to obliterate demand, cool down the economy, and corral inflation back under its 2% target. The full effect of those hikes are yet to be seen, but the PCE Price Index has dropped from 6.98% in June to 5.38% in January and PCE Core has dropped from 5.42% in February to 4.71% in January. And while monthly job gains have remained strong, labor demand has dropped 26% since last spring, as measured by LinkUp's job market data (U.S. job openings indexed every day directly from company websites globally).

But as we noted last September, unlike the jobless recovery of 2010-2015 which was entirely a phenomena of demand, the post-pandemic recovery has always been centered entirely around supply - the supply of goods (2021), then services (2022), and throughout, the supply of labor.

At this stage in the post-pandemic recovery, the economy has cooled and will continue to do so as the Fed's past and (hopefully modest and increasingly sparse) future hikes take effect, supply-chain issues have been resolved, and inflation is coming down.

Regarding the job market, always the fulcrum upon which the present state of affairs rests, the bid-ask spread between employers and employees has narrowed considerably and there is now significantly greater equilibrium between supply and demand. The rate of wage inflation has plateaued as wages stabilize at a higher level, hybrid work (where feasible) becomes the new normal, companies aggressively adapt their businesses to conform to the new world, and employers begin to find it easier to fill openings. The immaterial trickle of layoffs (mostly in tech), while great for alarmist headlines, simply supply much-sought-after, high-value talent back into the job market for employers to immediately snatch up.

But as graceful as this soft landing has been to this point (and should continue to be barring any reckless, unnecessary moves by the Fed), wage inflation is likely to persist indefinitely, once it settles into its new normal, within a range somewhere between 3-4% due to not only the permanent impact from the pandemic but also immutable demographic issues and other broader, structural issues affecting the job market.

That step-function upward shift in wage inflation is eventually going to necessitate the Fed raising its long-standing but increasingly outdated 2% inflation target. It should also trigger significant investment, alongside the investment in technology, robotics, automation, and AI that will most assuredly be happening, in substantially strengthening America's workforce, growing labor supply, and bringing more liquidity into the job market.

As Mohamed El-Erian wrote in a recent op-ed in the Financial Times:

"In my opinion, the fundamental medium-term characterization of the U.S. economy has shifted from one of deficient aggregate demand to one of deficient aggregate supply. Yes, the pandemic contributed to this but there is a lot more going on.

Some of the driving forces include the overdue green transition in energy and elsewhere, changing globalization, a multiyear quest to enhance supply chain resilience and a labor market that struggles to fill a record excess of job openings.

Those who agree the supply side of the domestic and global economy is most deterministic for inflation, growth and social outcomes immediately confront two tricky issues. One is what to do about a Fed inflation target that is too low for such a world and yet hard to revise given that the world’s most important central bank has already undermined its credibility. The second is how to better incorporate policymaking agencies beyond the Fed in a co-ordinated fight against inflation."

Unfortunately, the debate about the Fed's 2% inflation target is barely audible and, with the clown show in the House, expecting anything from Washington designed to grow and strengthen America's workforce is laughable. And if next week's jobs report comes in anywhere near the gain of 365,000 jobs we expect to see for February, the debate is a long, long way away from shifting from demand to supply.

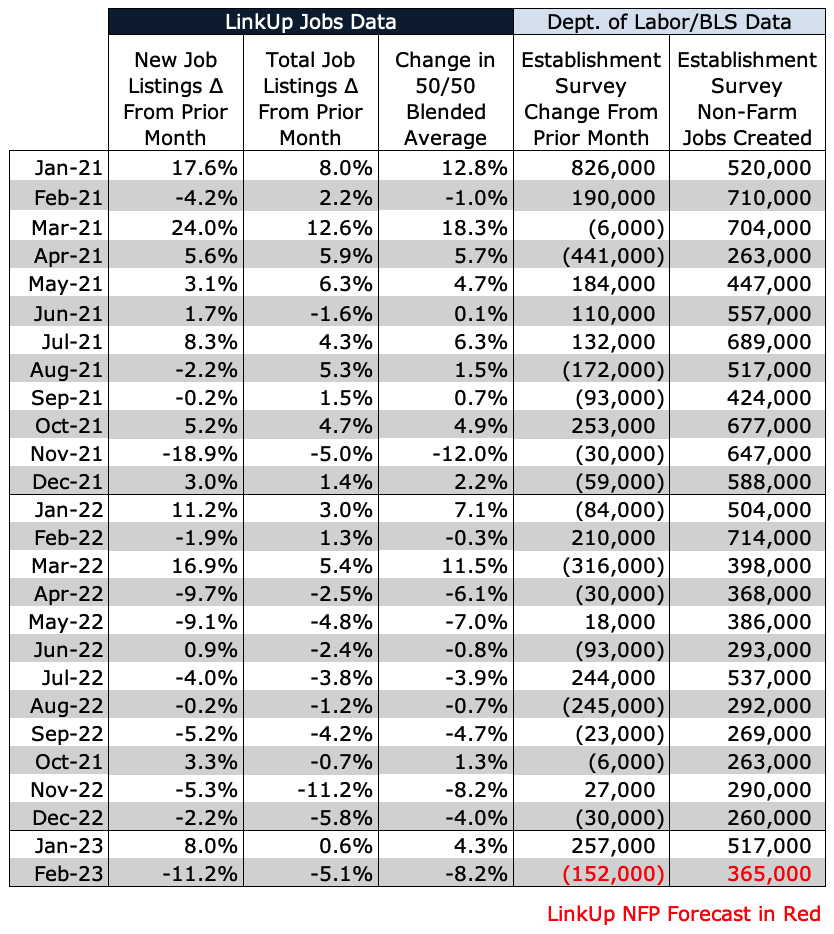

In February, total U.S. job openings indexed directly from company websites globally fell 5% while new job openings dropped 11% and removed job openings fell 1%.

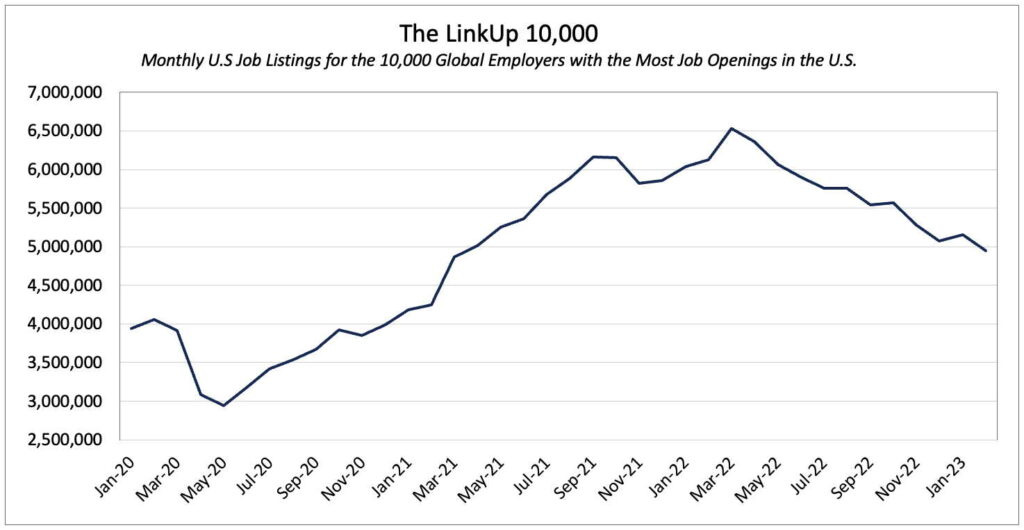

The LinkUp 10,000, which tracks U.S. job vacancies for the 10,000 global employers with the most openings in the U.S., fell 4% in February.

In February, new job openings fell in all but 5 states.

Labor demand declined in both manufacturing and services industries.

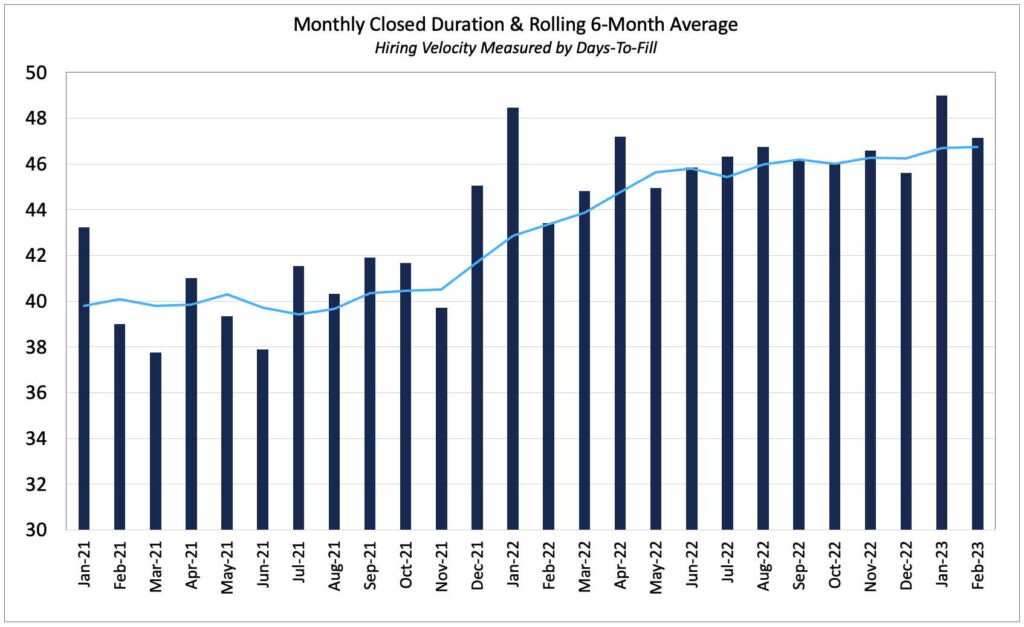

And lastly, hiring velocity increased, as LinkUp's Closed Duration or 'Time-To-Fill' metric for February dropped from 49 days in December to 47 days in February.

Based on our data and despite the continued decline in labor demand, we are forecasting a net gain of 365,000 jobs in February. This dichotomy between declining labor demand and continued robust monthly job gains is a topic we’ll return to in subsequent posts, especially given the bleak and pessimistic but highly flawed assessments offered by those relying solely on noisy job board data, but for now we’ll leave it there.

If one thought the debate around the economy and the Fed's ability to navigate through it wasn't deafening enough, wait until next week's jobs report comes out.