It’s Now Just Job Vacancies. The Rest Is Noise.

Job openings are the single most potent metric that captures the balance between supply and demand in the labor market

As intense as the focus has been on the labor market of late, that intensity sharpened further with the recent inflation report for August, the subsequent 75bp rate hike by the Fed, and the FOMC press conference that followed. As the country and the economy move further into a post-covid environment (and by post-covid, I mean that we’ve largely accepted covid as a permanent aspect of life and adapted to this new normal as such), supply chain issues are fading, the world is (sadly) beginning to adapt to the war in Europe, and the economy is down-shifting to a less torrid pace (arguably due, at least in part, to the Fed’s previous hikes).

But as things start to normalize (if anything today could be called normal) and slow down (and no, we are not in a recession – not yet anyway) and the temporary contributors to inflation begin to subside, job growth remains strong and wages continue to rise. This has incited a growing fear (and panic among those who believed that the Fed would begin lowering rates in early 2023) that the Fed, if it wasn’t already hell-bent on driving the economy into a recession, will be forced to do so in order to get inflation under control. Some had been even fanning the flames of hysteria by noting that the possibility of a 1% hike was (is?) on the table.

Amid the hysteria, however, it’s become absolutely clear, for those who weren’t already aware, that the labor market is the thing.

As Jeanna Smialek wrote this week in an article entitled New Inflation Developments Are Rattling Markets and Economists. Here’s Why.,

“As those [pandemic-driven] sources of inflation show early signs of fading, the question is how much overall price increases will abate. And the answer is likely to be driven in part by what happens in one crucial area: the labor market. Federal Reserve officials are laser-focused on job gains and wage growth as they quickly raise interest rates to constrain the economy and slow rapid price increases. Officials are convinced that they must sap the economy of some of its momentum to wrestle the worst inflation in four decades back down to their goal of 2 percent.”

The article continues…

“The bigger question for the Fed is not: Has inflation peaked? It’s: What’s the destination?” said Aneta Markowska, the chief financial economist at Jefferies. She estimates that it will be hard to get inflation below 4 percent — roughly twice the Fed’s average goal of 2 percent — without a substantial slowdown in the economy and labor market.

“You still have housing and the labor market, and there’s still a lot of inflationary pressure radiating from those two areas, which are very unbalanced,” Ms. Markowska said. That is why the Fed, which meets next week, is scrambling to bring supply and demand back into balance.”

So within the vast engine that is the U.S. economy, truly one of Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects – something so large it defies true understanding – it is the labor market that is the primary (if not the sole) indicator of the level at which that engine is performing and whether or not it is heating up or cooling down.

And as everyone knows, that sub-component, just like the entire engine of the U.S. economy itself, is comprised, at the highest level, of two parts – demand and supply. Rarely, if ever, are those two components in equilibrium, so the gauges measuring the job market (along with those that measure the broader economy) are used to determine the relative balance between the two (which side of the never-ending see-saw is dominant at the moment), the severity of the imbalance, which way things are trending, and the characteristics of the see-saw’s movement (velocity and volatility). And wrapped around all of this is everyone’s confidence in the gauges’ readings, the context within which the engine is operating (what’s happening in the world), and the predictability of what is going to happen with the engine.

Needless to say, we’re in insanely uncharted territory in terms of the broader context around the economy these days and the dynamics of both the broader economy and job market today couldn’t possibly be more dissimilar than what we went through during the nation’s previous recovery in 2010-2015.

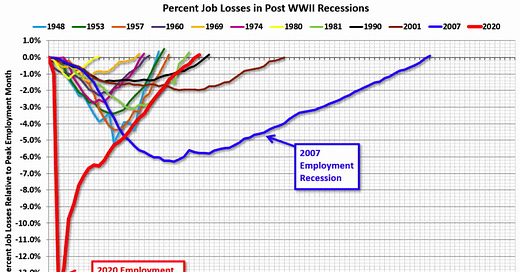

As we’ve highlighted repeatedly, the financial meltdown and the Great Recession that followed was characterized by the complete obliteration of demand everywhere (business and consumer demand alike across the entire country) but most pointedly in the job market where demand for workers plummeted and unemployment rose sharply.

The subsequent recovery was so slow and so gradual that it became known as the ‘Jobless Recovery.’ Supply of goods, services, and labor was always abundant during the period, and because employers never had to deal with labor supply as demand was slowly restored, they effectively never had to raise wages or make any concessions to attract workers. Throughout the entire era, the performance of the job market and the entire economic engine was always a function of no demand.

Today, things couldn’t be more opposite.

The pandemic annihilated supply everywhere (demand would have also been crushed were it not for the immediate and hyper-aggressive response from Washington). With no one able to work in person but everyone still earning income, supply of goods and services plummeted while demand remained solid. Then, as vaccination rates rose sufficiently, the ability to return to work in person was restored but the Great Resignation kicked in and labor supply effectively remained obliterated.

To entice workers back into the workforce and back to work in person, and to prevent them from quitting, employers have had to make all kinds of concessions, most notably around wages, to meet insatiable demand. To be sure, that’s a highly summarized synopsis and there were, and still are, plenty of significantly impactful nuances surrounding the era, but throughout the past 30 months, the economy and the job market have entirely been a function of no supply.

In addition to the polar opposite demand-supply characteristics of the two eras, they were also vastly different in terms of the underlying cause, the fiscal and monetary response, and the speed of recovery in terms of the broader economy generally and the job market specifically.

As always, no chart highlights the two differing employment recessions more starkly that CalculatedRisk’s ‘Scariest Chart Ever.’

So while it’s the current era’s rapid recovery amid supply issues (along with a war and corporate price-gouging) that have driven up inflation, demand reduction (hopefully not demand destruction) will be the vehicle by which the Fed restores balance. And as noted previously, the Fed is solely focused on reducing labor demand, ideally through a soft landing – a decline in job openings rather than an increase in unemployment. As a result, the Fed is lasered in on job vacancies as the most critical gauge in the war on inflation.

During the Fed Chair’s press conference following the FOMC rate hike, there was this exchange:

RACHEL SIEGEL [Washington Post]: Are vacancies still at the top of your list in terms of understanding the labor market?

CHAIR POWELL: Yes

So job vacancies are all that matters – they are the single most potent metric that captures the balance between supply and demand in the labor market. Everything else is either a secondary, lagging consequence of the imbalance between labor demand and supply (job growth, wage growth, unemployment rate, unemployment filings, etc.) or a tertiary indicator of the inner-workings deep under the hood of the nation’s job market engine (labor force participation rate, employment population ratio, quits, etc.).

As Jan Hatzius, Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs, noted on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast in August:

“The big issue on inflation is labor market imbalance and job vacancies are the key to understanding labor market imbalance. If I had defined Full Employment a year and a half ago, I would have talked about unemployment rate and employment population ratio but open positions would have only had a supporting role. Now, job openings are playing a much more central role because they basically give you the balance between total labor demand and total labor supply.”

As we’ve been highlighting for the past 5 months, the labor market, while still very strong, is most definitely cooling off. Since March, U.S. job openings indexed directly from company websites globally have dropped 11.9%. We’ll post our monthly job vacancies data for September on Monday, October 3rd, along with our official non-farm payroll forecast for September, but because job openings are predictive of job gains in future periods, our September NFP forecast is based on LinkUp’s August data and at this point, our preliminary forecast for September is a net gain of 275,000 jobs.

But far more important than our forecast on the 3rd will be our job openings data for September. As we’ve noted at length above, job vacancies are all that matters – they are the thing. Pertaining to the labor market, inflation, and Fed policy, nothing else matters.

As Jamie XX says, The Rest Is Noise.