LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 460,000 Jobs In March

Strong Job Growth Would Mark Continued Progress for the Most Glorious of Soft Landings

Given the post-pandemic tumult, it shouldn't be surprising to anyone that 2023 is proving to be as chaotic and unpredictable as the prior two years. January's recession paranoia turned on a dime to February's panic over how high rates had to go to quell an untamable job market, and with SVB's meltdown in March, the focus shifted to the fragility of the banks, a risk factor seemingly on nobody's radar.

But the job market was nudged off center-stage for less than a week as discussion quickly turned to the extent to which reduced bank lending would effectively act as another cannon barrage against the ongoing battle against the evil axis of inflation, strong job growth, and profligate consumers. The job market further solidified its position back in the spotlight as the bank contagion discussion converged with the NAIRU discussion, adding a few more decibels to the growing chorus calling for a rethink of the Fed's 2% inflation target. As John Plunder wrote in an Op-ed in the Financial Times recently:

We may now be at just the start of a series of financial instability episodes which will add to the risk that in trying to wrest inflation back to 2 per cent, the Fed and other central banks will do serious damage to output and employment.

No surprise, then, that there is a growing chorus arguing for raising inflation targets from 2 to 3 per cent. Nor is this unreasonable if, as former Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane has argued, we are witnessing a shift upwards in the global equilibrium price level. There is anyway no theoretical justification for equating 2 per cent with price stability.

Unfortunately, even as that chorus gains a few more voices, we anticipate, just as we did last month, that it will continue to get drowned out with Friday's jobs report for March where we expect to see net job gains of 460,000 for the month. And what shame that things are likely to play out this month similarly to how they did last month, albeit with even more intensity, with nearly everyone vociferously advocating for relentless and aggressive rate hikes to crush demand and very little support for doing anything to substantively increase supply.

As we wrote last month prior to February's jobs report, "Unfortunately, the debate about the Fed's 2% inflation target is barely audible [and] if next week's jobs report comes in anywhere near the gain of 365,000 jobs we expect to see for February, the debate is a long, long way away from shifting from demand to supply."

February's job gains came in far higher than most everyone expected even as unemployment ticked up a notch, and the subsequent consensus on Wall Street was perfectly captured by a Chief U.S. Economist at a large U.S. bank who stated that February's jobs report was "exactly what I wasn’t hoping for which is a mixed report."

The characterization that February's jobs report was confusing, inconclusive, or anything less than ideal couldn't be further off the mark. As we've been saying for nearly two years, reports like February's are exactly what we've been expecting and hoping for as the soft landing becomes increasingly realized.

The disequilibrium in the job market, created by the seismic bid-ask chasm between employers and employees following the epic pandemic earthquake, has narrowed considerably as employers, by conceding to every demand from America's workers, added an average net gain of 340,000 jobs per month since last April when the Fed began hiking rates, wage growth has since tapered off, the economy is now cooling down, inflation continues to drop, and unemployment has barely budged off its 50-year low.

How is this picture anything but stellar?

And nearly as baffling, why is the manner in which this scenario plays out confounding to anyone? It is precisely how markets work - sufficiently committed buyers and sellers negotiating over terms until a mutually agreeable price is reached.

Granted, when the market consists of millions of employers and 150 million individual workers (all of them, for now, human beings), the terms being negotiated consist of an extraordinarily large, highly varied, and perpetually shifting set of elements, and the timeframe spans years (and actually never ends), the market in question is arguably the world's most complex.

And of course, the negotiations always take place in the broader context of the moment and this uncharted, post-pandemic moment is particularly fraught with complexity even without accounting for a European war, wildly noisy and dysfunctional polarization, accelerating disruption from technology and climate change, increasingly unreliable 'official data,' and epic demographic trends, among other things.

So I suppose some latitude around uncertainty should be granted.

But Occam's Razor, the simplest answer typically being the best, is the key to understanding the mechanisms inherent in this exceedingly complex market. Buyers meet the demands of sellers by strengthening their bid (wages, benefits, remote & hybrid work, work conditions, career paths, corporate culture, etc.) and a certain number of sellers accept. Demand persists among remaining buyers still in the market who then further strengthen their bid, resulting in an additional set of sellers accepting the new, raised offer.

This plays out over months and months, with each subsequent wave of raised bids resulting in higher wages and better terms until increasingly large numbers of buyers and sellers have reached or are now reaching a mutually agreeable price for their employment. This growing equilibrium between supply and demand, between buyers and sellers, is precisely where we are now and the result is that employers/buyers have put bids on the table that are generating large waves of job seekers/sellers accepting jobs.

And the market is finally getting cleared out.

Because each wave of strengthened bids brought new people into the market (and also enticed people to quit in elevated numbers to take better offers elsewhere), unemployment has remained flat at or near historic lows.

Likewise, as each wave of stronger bids results in solid monthly job gains, demand gets increasingly sated, the need to keep raising the offer declines, and upward pressure on wages softens. For certain, the Fed hikes have had, and will likely continue having, an impact in reducing demand given their long-term life-span, and sellers, too, are more willing now to accept current offers given the economy's increasing uncertainty and the growing specter of not having a chair to sit on when the sweet tune of increasingly attractive bids finally stops, which, at some point, it inevitably will.

In its simplest form, the basic mechanics of the job market, or any market for that matter, are not difficult concepts to understand. What is exceedingly difficult, however, is the the sheer size of the job market, the seemingly intractable illiquidity calcified into it, the impossible number of variables motivating market participants, inadequate, lagging government data, and the impact of external factors on the market itself. On top of all this, everyone evaluates the market from their own perspective and with their own biases, motivations, beliefs, and preconceived ideas.

And then, of course, there is the small matter of trying to predict the future - rarely an easy assignment. But armed with the largest, most accurate job market data indexed directly from company websites globally, we're committed, nonetheless, and with our forecast of 460,000 jobs gained in March, nearly double consensus estimates, we expect the ferocity, din, and chaos of the debate around Fed policy to reach unprecedented levels in the weeks ahead.

So turning to LinkUp's data, in March, total U.S. job openings indexed directly from company websites globally rose 6% while new and removed job openings skyrocketed each jumped 22%.

The LinkUp 10,000, which tracks U.S. job vacancies for the 10,000 global employers with the most openings in the U.S., rose 7% in March.

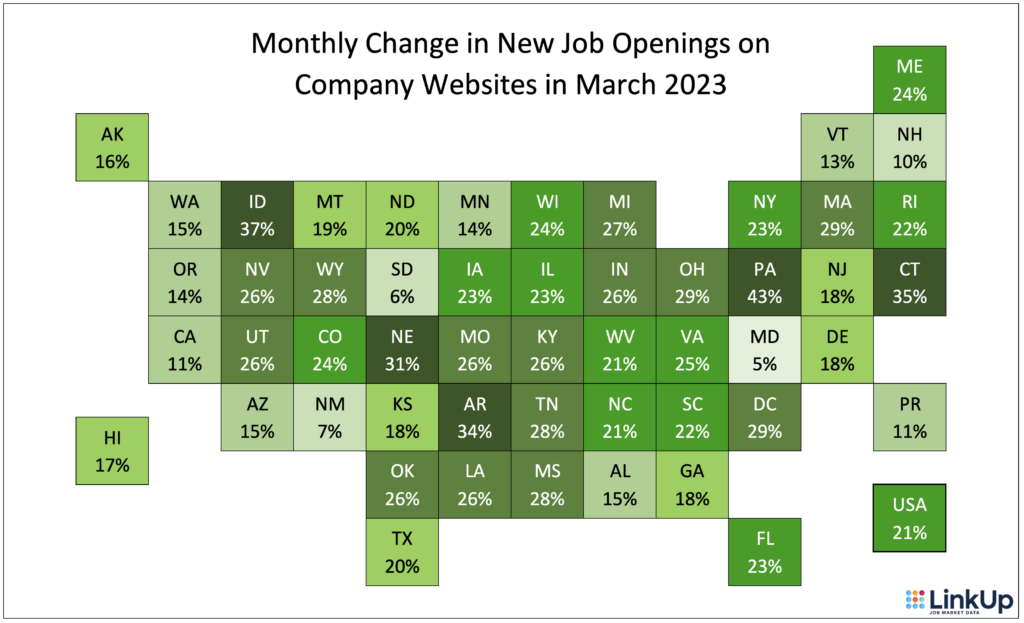

In March, new job openings skyrocketed throughout the country with gains ranging from 5% in Maryland to 43% in Pennsylvania.

Labor demand rose in both manufacturing and services industries with sharper gains in services.

The largest increases in job openings all occurred in service sectors including Retail and Wholesale Trade, Transportation, Education, Construction, Healthcare, and Accommodation and Food Services.

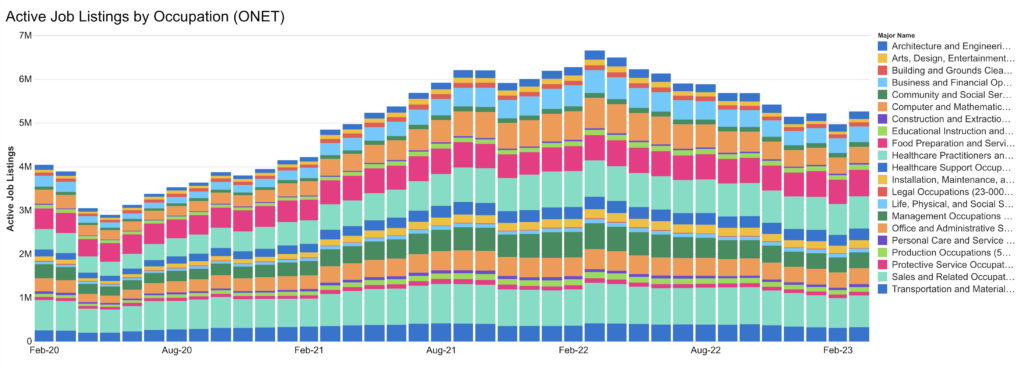

Consistent with the above, occupations with the largest increase in job openings included Personal Care & Services, Arts, Design & Entertainment, Education, and Cleaning & Maintenance.

And lastly, hiring velocity stayed relatively flat compared to February, as LinkUp's Closed Duration or 'Time-To-Fill' metric for March rose by just half a day from February.

Through March 20th, hiring among the S&P 500 was essentially flat for the month, with all sectors falling during the month with the sole exception of Consumer Discretionary.

Based on our data, we are forecasting a net gain of 460,000 jobs in March.

We'll end (sort of) this month's post the same way we ended last month's when we stated, "If one thought the debate around the economy and the Fed's ability to navigate through it wasn't deafening enough, wait until [this] week's jobs report comes out.” True a month ago and even truer now.

If we're in the ballpark with our forecast, we'd make one additional point with a reminder to keep the larger and simpler picture in mind as to what those job gains represent: growing equilibrium in the job market and continued, steady progress in this most glorious of soft landings.

Let's hope we're right and, if so, cheer the outcome for the U.S. economy, its workers, and its employers.