LinkUp Forecasting Net Gain of 260,000 Jobs in April as Job Market Remains Resilient

Growing equilibrium in the job market has helped the Fed achieve a very soft landing

Among the growing preponderance of aspects of life that have been or are becoming hyper exaggerated to an absurd degree these days, one of the more perplexing is the disconnect between perception and reality around the state of the U.S. economy. Between the media, public opinion surveys, and consumer confidence polls, one might assume the pandemic had morphed into a ‘Last of Us’ apocalyptic hellscape plagued by mushroom monsters.

But as Matthew Winkler recently wrote in a Bloomberg op-ed, nothing could be further from the truth. In the past 27 months,

“the U.S. has experienced the greatest and fastest GDP recovery in modern times, paving the way for record corporate earnings, the lowest corporate debt ratios, rising real incomes, surging homeowners' equity in real estate to go along with the lowest mortgage delinquency rate on record, and household checking accounts flush with some $5 trillion of cash. And, no, your 401K has not suffered under Biden; the benchmark S&P 500 Index is up 23% since the November 2020 election.”

Winkler goes on to write:

“For all that, the labor market is the real star. No president since Lyndon Johnson can match Biden's record here. He has created the equivalent of six times more jobs than the last three Republican presidents combined. Some 824,000 jobs were created alone in the high-paying manufacturing sector amid the biggest commitment to rebuilding roads, airports, bridges and ports since the Eisenhower administration’s new national highways. We have a jobless rate that is the lowest in a peacetime economy since World War II, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Consider that unemployment is at all-time lows in 24 states and less than 3% in 21, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The unemployment rate for Blacks has never been lower, nor has the gap with the overall jobless rate been narrower.”

And while all that has been going on, inflation has been steadily coming down and employment has not budged one iota from its near-record low.

Is anyone really still not seeing the soft landing?

As we wrote in February, the soft landing has already been achieved, and the only remaining question at the time was (and, to a large extent, still is) whether or not we we’ll all be allowed to de-plane calmly and safely through the gangway.

On that point, we anticipate (and hope) that multiple data points this week will point to precisely that happening. Between job openings, inflation, Fed guidance about future hikes, and Friday’s jobs report for April, it should become even clearer that after tomorrow’s 25bp hike, the Fed must pause for a sufficient period of time to assess whether or not any additional rate hikes are necessary.

We do expect, however, that the Fed’s patience will be tested to some degree with Friday’s jobs report where we expect a net gain of 260,000 jobs in April, slightly up from March and above consensus forecast.

But in having its patience tested, the Fed need not flinch. As we wrote last month, solid monthly job gains that are approximately consistent with historical averages, even if they are modestly above consensus estimates, should not be surprising given the present job market dynamics and are nothing to get too worked up about.

Over the past two years, the massive bid-ask spread between employers and employees has been bridged almost entirely by the string of escalating concessions (wages, benefits, remote & hybrid work, work conditions, career paths, corporate culture, etc.) that employers made to strengthen their bids which, in the aggregate, accumulated to become significantly more material than anything seen in 50+ years.

As a result, ever-increasing numbers of people have returned to the job market (or switched to more attractive jobs) while at the same time, layoffs have increased critical labor supply and employers have become more efficient and adapted to a permanently altered, post-pandemic employment landscape.

Due to all of those factors, greater and greater equilibrium has been steadily restored to the job market.

With increased equilibrium, wage inflation, in turn, has largely tapered off as the pressure on employers to continue to improve their bids has subsided. Quit rates have returned to normal levels, outsized gains by job switchers have largely disappeared, and employers are finding it easier to fill openings than at any point in the past few years.

As wage inflation has subsided, combined with the fact that the transitory causes of inflation did evaporate as many expected they would, broader inflation has plummeted despite the fact that corporate profits stand at record levels.

To be sure, wages are most definitely still rising in certain pockets of the economy where huge, unmet demand persists, most notably in the service sector, to fill the lowest paying jobs in the economy, a phenomena that is likely to continue until those employers raise wages voluntarily or by force or they eliminate labor demand through automation, robotics, AI, or obsolescence.

Or perhaps, just maybe, as a society, we decide that people deserve to earn a livable wage. And maybe, just maybe, the Fed determines that livable wages and setting prices for goods and services in a manner that accurately reflects true costs in a way that’s best for society as a whole might necessitate raising its inflation target from an arbitrary and deeply flawed 2% target. Wait….what planet am I on?

So while declining labor demand will eventually result in smaller and smaller monthly job gains and an end, at some point, to this awesome streak of consecutive monthly job gains that now stands at 27, we don’t see it happening anytime soon.

For now, we’ll just keep chuckling as the pessimists keep pushing back the ETA of the most-anticipated-recession-that-never-arrives. (and to be clear, a recession/depression triggered by a U.S. default at the hands of the nihilist clowns in the House doesn’t count as a Fed-induced recession).

So as always, our March forecast is based on millions of job openings in the U.S. sourced directly every day from tens of thousands of company websites around the world. In April, total job openings in the U.S. fell 1.5%, new openings dropped 7.7%, and job openings removed from company websites fell 2.1%.

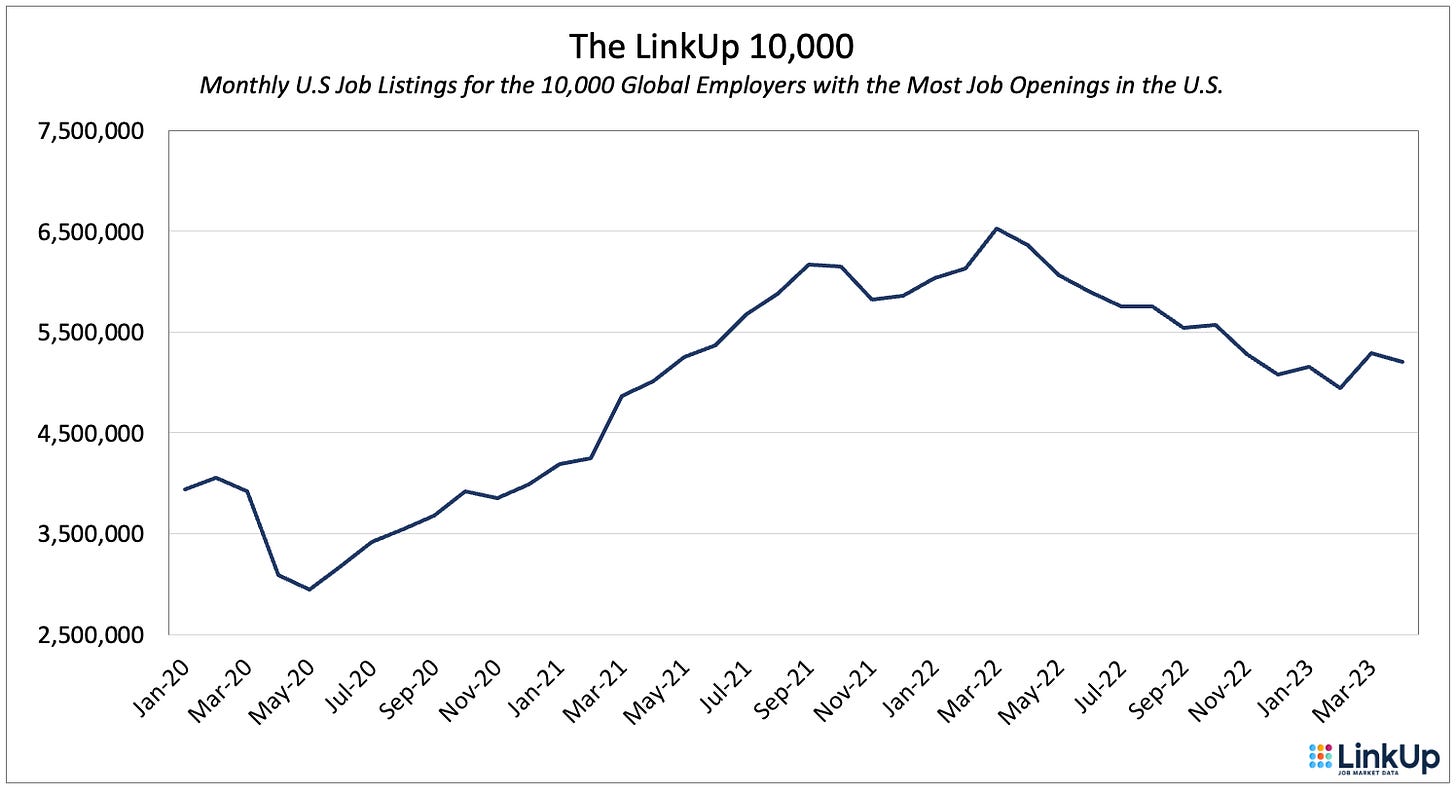

The LinkUp 10,000, which tracks U.S. job openings for the 10,000 global companies with the most openings in the U.S., also fell 1.5%.

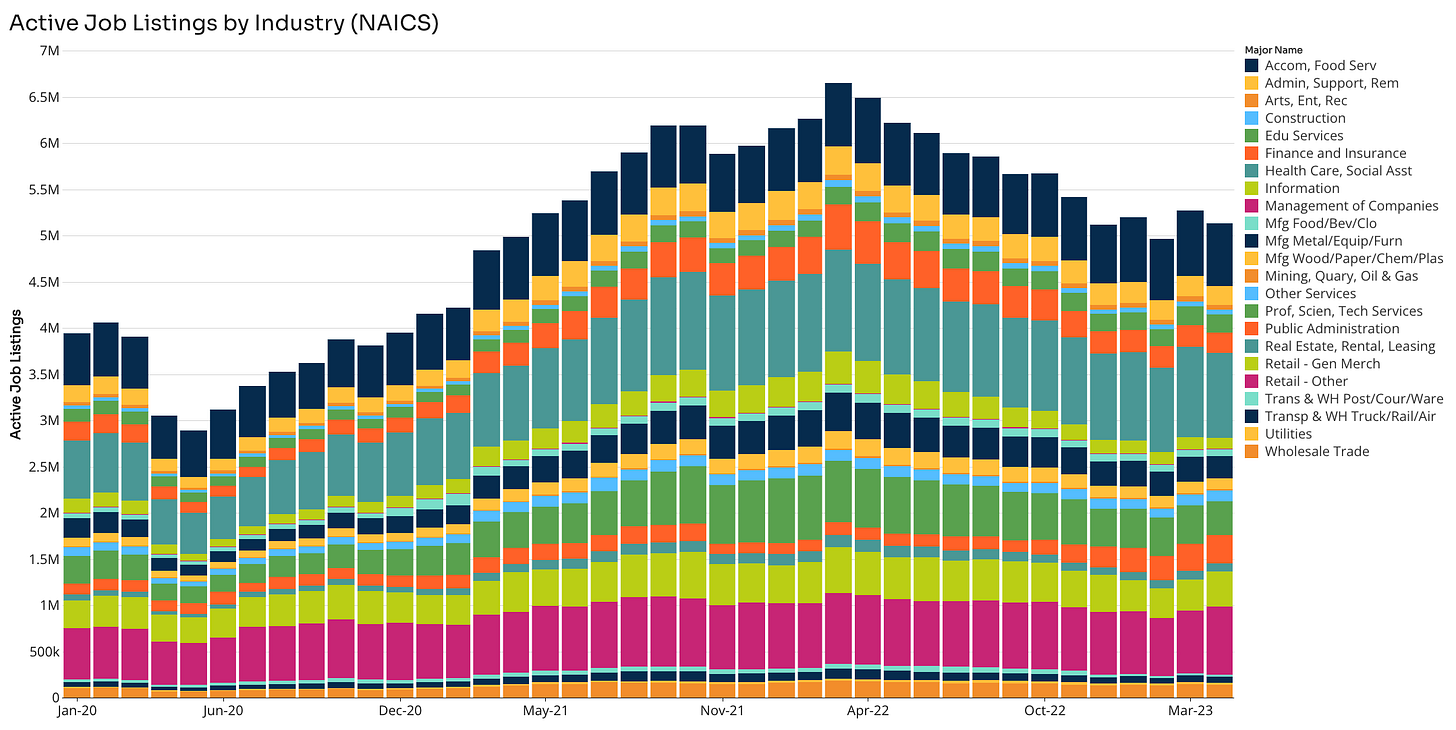

Job openings declined in both manufacturing and service industries and are now both roughly 30% above where they stood just before the pandemic hit.

By job openings rose the most in Retail and fell the most in Professional Services, Finance and Insurance, and Manufacturing.

By occupation, openings rose the most in Sales, Personal Care and Services, and Transportation, and dropped the most in Arts, Design, Media & Entertainment, Business & Financial Operations, Architecture, and Healthcare.

Across the country, new openings dropped by 8% with only 8 states showing an increase and 2 with 0% change.

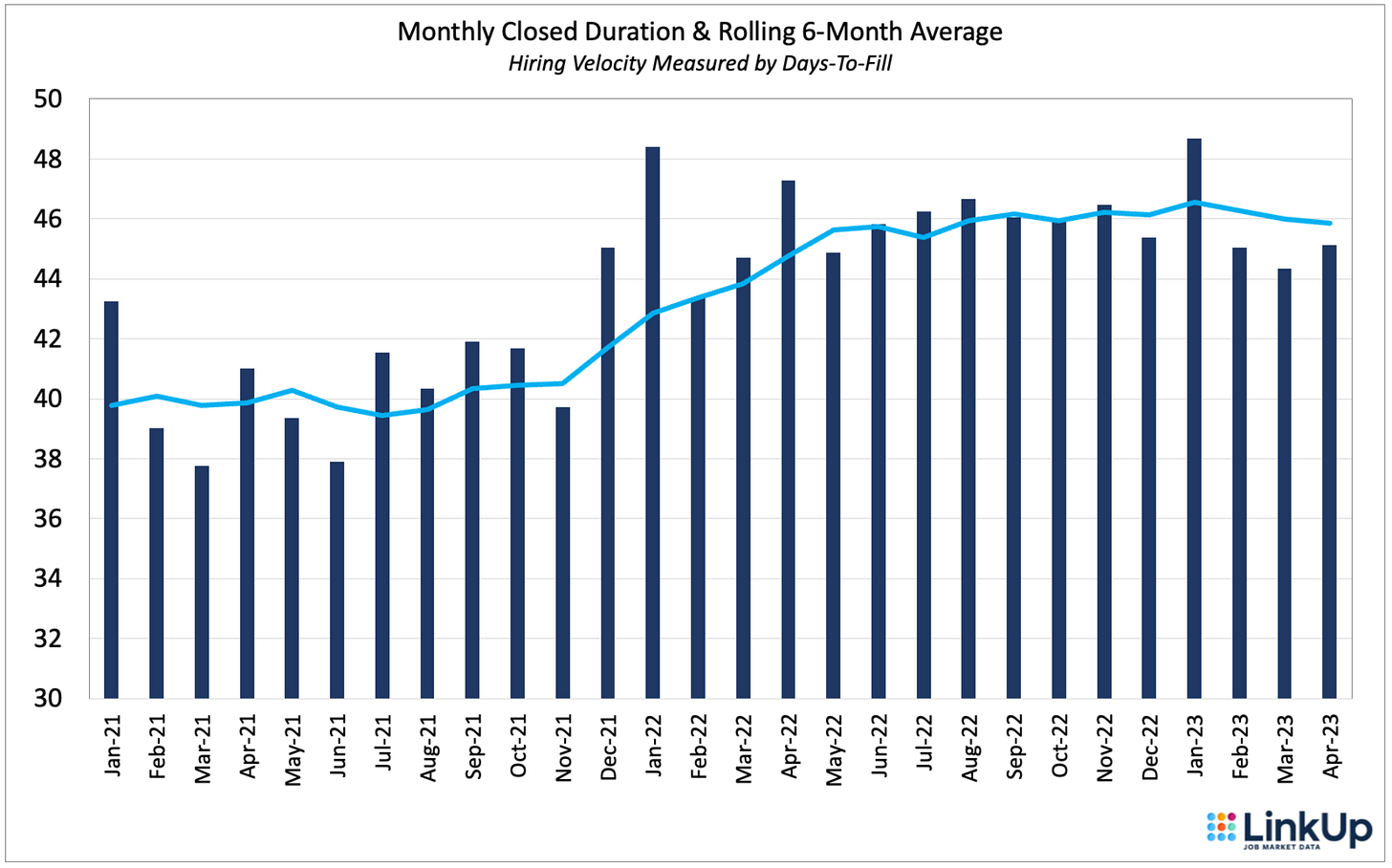

Across the entire economy, it took an average of 45 days for employers to fill openings in April - the long-term historical average ‘time-to-fill.’ The average hiring velocity of roughly 46 days for the past year or so provides further evidence that the job market has achieved a high degree of equilibrium.

As we wrote in a piece a few weeks ago about the myth of so-called ‘ghost’ jobs, we also break down our duration data by various duration ranges to track what’s driving duration as a whole, and there’s a noteworthy jump in both March and April in jobs that were removed after only having been posted for less than 30 days.

So based on job openings data for March and April, we are forecasting a net gain of 260,000 jobs in April, slightly up from March and well above the 180,000 consensus estimates.

And lastly, for those who might disregard the service sector and the lowest paying jobs in the economy and feel that people don’t deserve a livable wage, I’d recommend a fantastic documentary coming out soon on the nation’s agriculture and food service industries.

See it.