While a Recession Is Not in the Cards, The Fed Should Not Wait To Cut Rates

The job market has powered an enviable U.S. economy for the past 4 years but it’s time for the Fed to take over

We’ll publish our July non-farm payrolls forecast Thursday once we have complete data for July, but with the barrage of breathtaking headlines and data releases over the past week or so and given that we’re half way through what everyone knew would be a tumultuous year in every imaginable respect, we thought it would make sense to take a step back and assess where things sit YTD in advance of next week’s jobs report.

Starting with the recent spate of data, Q2 GDP came in at 2.8%, inflation dropped to 2.5%, nominal and real incomes rose, consumer spending ticked up, and unemployment claims keep bumping along the ocean floor.

So the irrefutable take-away is not, as the Associated Press characterized the economy this weekend, that the soft landing ‘is taking place…so far,’ (for those who missed it, the soft landing actually happened last year), but that a recession is nowhere in sight.

And yet the Fed, arguably being overly data-dependent, seems to be waiting for yet more proof that inflation has been pummeled into submission. How much more evidence do they need?

As the Financial Times recently noted:

Ever since the Federal Reserve signalled that the rate-rising phase of its historic fight against inflation was over, attention has been focused on when — and how quickly — the US central bank would provide relief to American borrowers.

Chair Jay Powell and his colleagues have said they need irrefutable proof that inflation, which at one point hovered around a four-decade high, is retreating to the Fed’s 2 per cent target. Until then, the Federal Open Market Committee would lack the confidence necessary to begin lowering interest rates.

A string of favourable inflation data — coupled with signs that the labour market has lost some of its earlier heat — suggests that high bar has more or less been met.

Given the recent past, it’s somewhat understandable that the Fed does not want to be surprised again like they were earlier this year when inflation flared up temporarily and, from their vantage point, surprisingly.

As FT noted in the same article, the Fed has “been headfaked before, and credibility is important,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at KPMG US.

After months of steady progress towards 2 per cent, first-quarter data showed an unwelcome resurgence in price pressures that cast doubt about the Fed’s grip on inflation and scuppered plans to begin cuts at the start of the summer. That was the latest in a series of economic surprises in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic in which officials were wrongfooted and forced to rethink their policy settings.

Being data-dependent is, at best, a double-edged sword when data is lagged, volatile, and noisy and, at worst, fraught with peril if critical data one is dependent on is flawed. Regarding criticality, as we’ve noted ad nauseam, we’d argue that nothing is more fundamental to understanding the economy than the job market and, furthermore, that no data is more important to understanding the job market than accurate and timely labor demand data. To that end, defective JOLTS data has proven to be a consistent source of both economic surprises and credibility impairment.

As the chart below highlights, a misfiring JOLTS signal, at a minimum, obscured the two most significant economic surprises in the Covid era:

1. No recession in 2023 (i.e., The Soft Landing)

2. Resurgent inflation in Q1 2024

In both periods, as the chart also clearly indicates, LinkUp’s comprehensive, highly accurate job openings data sourced directly from employer websites globally every day contrasted sharply with JOLTS data and very clearly signaled strong labor demand in the U.S. That strong demand led to much higher job gains than economists expected which, in turn, staved off a recession in the first instance and bolstered consumer and business spending in the second.

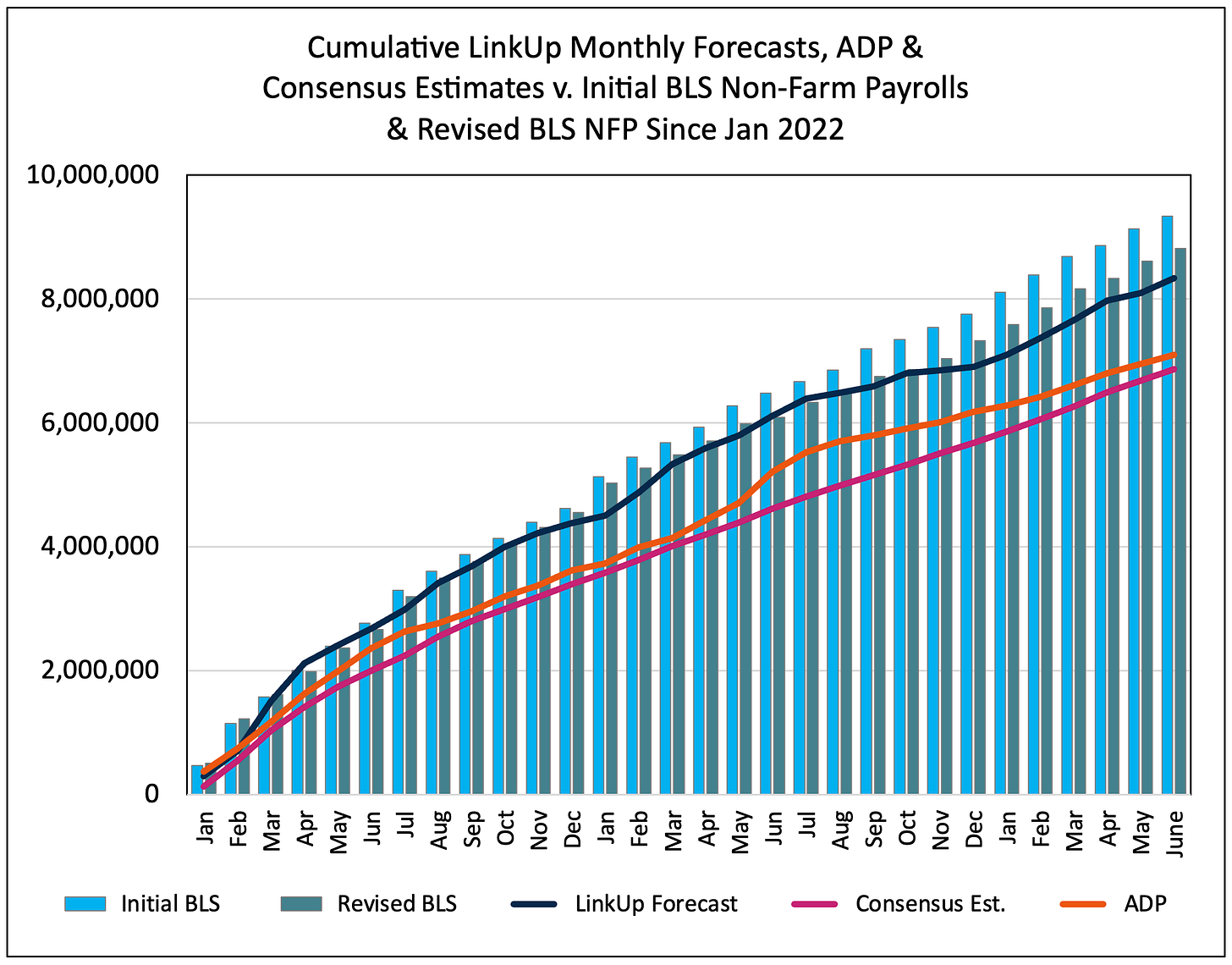

Lest anyone accuse us of 20/20 hindsight or missing the signal(s) in real time at those moments, we’d point to a scant 5% tracking error in our cumulative non-farm payrolls forecast since 2022 (not to mention essentially every blog post we’ve written since March of 2020).

For the first six months of the year, with our data showing an increase in labor demand of 4% (as opposed to JOLTS data showing a decline in labor demand of 8%), our tracking error is even better at just 2.8%.

In 5 of out the 6 months YTD, we forecasted job gains higher than consensus estimates and job gains did, in fact, come in higher than consensus estimates in 5 out of 6 months (we did, however, miss the one month aberrant month - April v. May).

More importantly and far more fundamentally, what our data shows is how perfectly balanced the U.S. job market is at the moment.

It is that perfectly balanced job market that we’ve been observing for some time, combined with the ever-expanding mountain of evidence that we see everywhere, that puts us firmly in the ‘Why Wait?’ camp - not because a recession looms on the horizon as many in our camp believe, but because we see a steady economy being held on its enviable course by a perfectly balanced job market and surrounded by a multitude of neutral rates. The Fed Funds rate is the final rate that can and needs to start coming back down into neutral territory (where that is precisely has been and will be much debated in the months ahead).

To be clear, we’re not oblivious of the same things everyone else sees that point to an economy that is cooling off from its over-heated condition in the aftermath of the pandemic, and the job market is no exception.

Wage inflation has tapered off, the household survey is flashing warning signs, unemployment has crept up slightly (arguably because more people have started looking for work and have not yet been absorbed into the workforce), and hiring velocity has slowed down.

So while we do not see a recession on the horizon, we are firmly anchored to the consensus view that Fed cuts are very much in order - the downside risk of higher unemployment has become sufficiently higher than the risk of inflation popping back up again. Our view has become further cemented by a recent exercise where we used our data to forecast various scenarios around job growth for the remainder of 2024.

Although our data is incredibly useful in accurately and fundamentally understanding the job market in real-time and forecasting job growth one or two months into the future, we typically do not forecast non-farm payrolls further out than 30 or 60 days due to the fact that one of the variables in our forecasting model is the most recent month’s BLS NFP number.

So in no way are the scenarios presented below our ‘official’ non-farm payrolls forecasts for any month between now and the end of the year. As mentioned at the outset, we’ll be publishing our official NFP forecast for July on August 1st and all subsequent ‘official’ forecasts will be published on a monthly basis on or shortly after the first of each month.

What the scenarios below are designed to do, however, is present a 6-month baseline scenario for job growth in the U.S. along with an upper and lower bound based on where things sit today as well as seasonality trends in our data from the prior 12 years (excluding 2020).

After normalizing our labor demand data and bucketing it into various time series over the past decade or so, we created what we’d posit as a baseline model using a 50/50 blend of the monthly averages between 2012-2023 and 2022-2023.

We also created an upper bound that assumes things track more closely to the most recent ‘Full Employment’ environment (2015-2019) given that we are now very much in similar circumstances and a lower bound that assumes things track along a path more comparable to what we’ve seen in the past 2 years.

Using this Total Job Openings model detailed above, combined with a similarly constructed model for New Job Openings (the second critical variable in our NFP forecasting model), we carried the data forward from June to arrive at the 3 job growth scenarios detailed in the chart below.

That baseline scenario results in average monthly job gains of 210,000 in Q3 (up from 177,000 in Q2) and 105,000 in Q4 and a total job gain in 2024 of 2.28 million. But the drop in Q4 and especially the net gain of just 10,000 jobs in December (which drops to -109,000 in the lower bound scenario) are particularly alarming. It’s that ‘normal’ trajectory in the baseline model that underlies the concern of the ‘cut now’ proponents.

The other way to potentially think about the 3 scenarios that we modeled is in the context of when the Fed makes its first cut. We’d hypothesize that the baseline model would be similar to what would happen with a September cut, while the upper bound would be a cut next week and the lower bound would be no cut in September.

Given that our baseline model looks quite distressing even without the inevitability of a recession and even with a September cut factored in, we are of the mind that the Fed should make its first cut immediately.

The economy is in solid shape today, it’s likely cooled off enough such that an unexpected cut in July would not reignite inflation, and the downside risk of a rapidly deteriorating job market is way too high. The job market has powered the U.S. economy for the past 4 years but we share the view of those quoted in the same FT article cited above - it’s time for the Fed to take over.

“Because the labour market was so resilient, [The Fed] thought they had the luxury of time to be super sure [about inflation],” said Julia Coronado, Founder & President of MacroPolicy Perspectives. “That luxury is fading.”

Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, has gone so far as to argue that waiting until September raises the risk of the very outcome the Fed is trying to avoid.

“If you wait, there is a risk on the economic side that you see more of a deterioration in the labour market,” he said. “Given how much things have changed — how much inflation has come down and how much the labour market has rebalanced — why wouldn’t you just get ahead of what you’re probably going to do anyway?”

P.S. - speaking of forecasts and predictions, there’s no way I can resist pointing to prediction #11 in my 10 predictions for 2024 in January:

#11 - Neither Biden nor Trump will be their party’s nominee in November.

Even 50% correct on that one is way above an A+ and there is still plenty of time before November to get the remaining 50% correct.

Moses - You are correct. LinkUp's data shows 4.93M job openings in June in the U.S. as compared to JOLTS which came in today at 8.18M. I'd argue, however, that for multiple reasons the JOLTS number is inflated to some extent based on their methodology. My best estimate of the actual number of openings (and it is admittedly an entirely unknowable number) in the U.S. at the moment would be around 6.6M job openings. Finally, I'd say that the signal or insight in our data resides in the trend line of our data, especially relative to JOLTS data which is also released a month later than LinkUp's data.

What does the rhs axis mean in the jolts v. linkup chart? Does linkup show 5M v. 8m?